SMi Source lesson Multiple Sclerosis has the following microlearning topics

1. Introduction

2. Classification

3. Signs and Symptoms

4. Diagnosis

5. Prognosis

6. Pathophysiology

7. Current Therapies

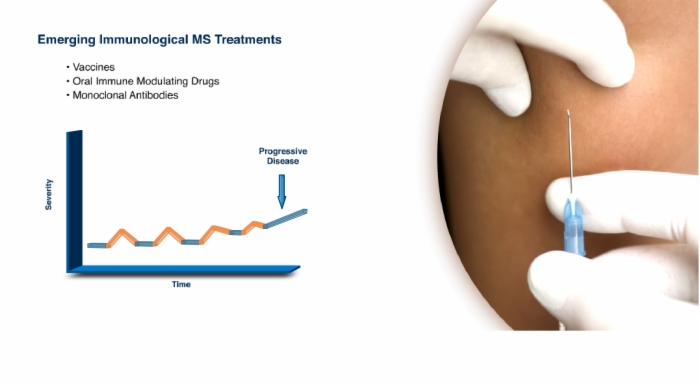

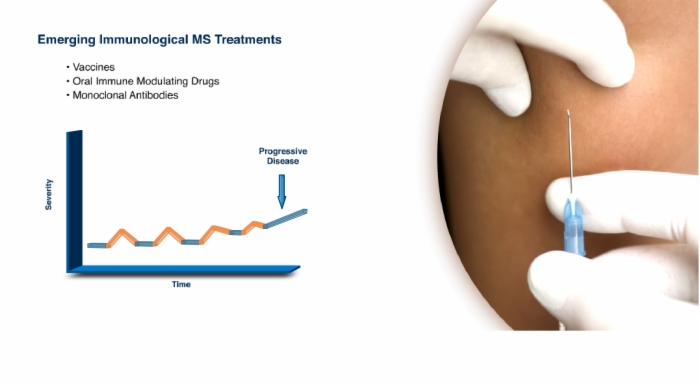

8. Emerging Hypotheses on Treatment

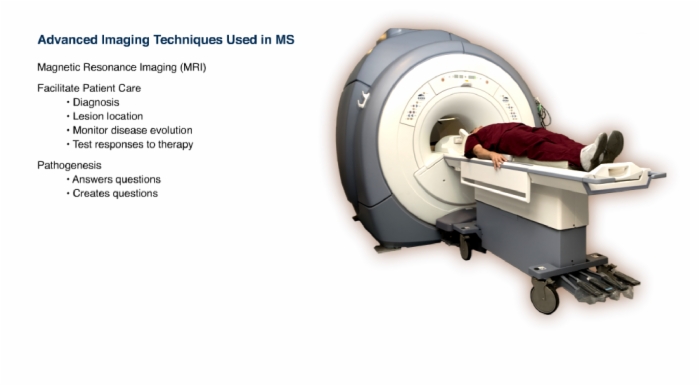

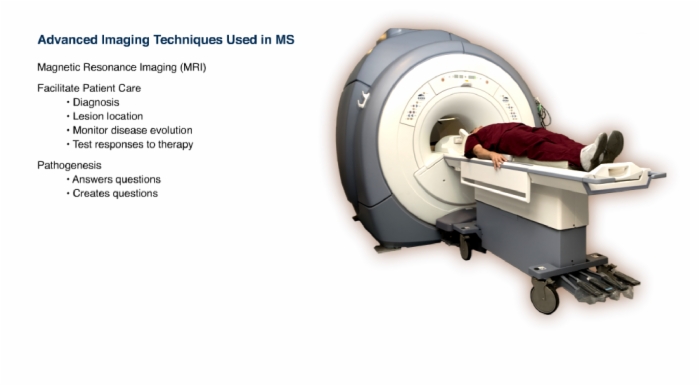

9. Advancing Technologies

Lesson Multiple Sclerosis addresses these key points

- Variable

- Mortality is slightly higher with MS vs. general population

- Survival for MS is long - 20 to 45 years from onset of symptoms

- Number of years of life lost - 5 to 10 years

- MS has been around for at least several hundreds of years.

- Around 1868, identified as a distinct disease.

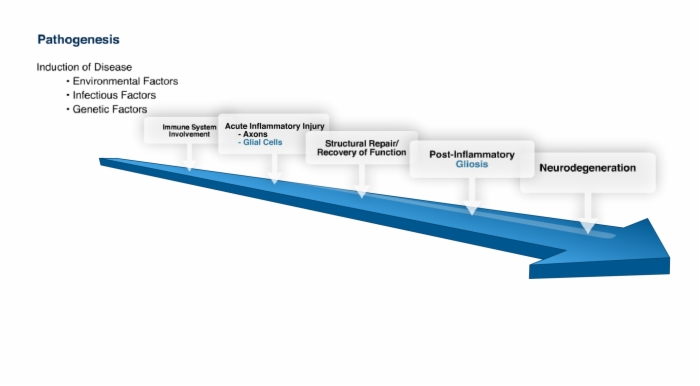

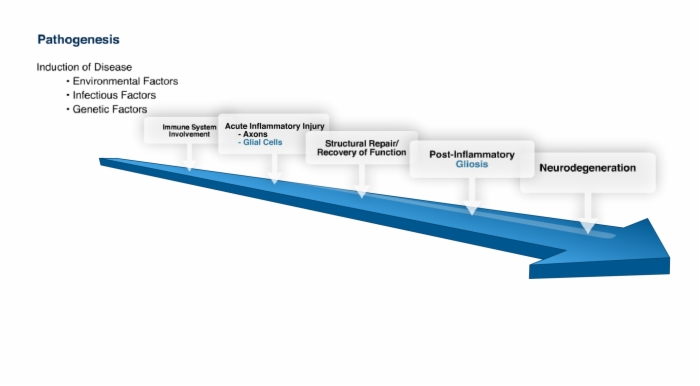

Causes of multiple sclerosis remain unknown. Contributing factors are: environment, infection, genetics and immune system.

Each could contribute to initiation of disease, relapses and progression of disease.

Over the years, almost every class of microorganism has been investigated for MS disease association, including:

- Viruses

- Bacteria

- Chlamydia

- Mycoplasma - Fungi

- Rickettsia

- Parasites

Twin studies provide strong evidence for a genetic role in susceptibility to MS. These studies have shown 20-60% concordance of MS in identical twins, and 2-5% concordance in like-sex fraternal twins, traditional siblings, or children of individuals with MS.

The only genes that have been identified to have a strong association with MS are the class II major histocompatibility complex, or class II MH, genes.

Protein products of these genes are self antigens that are involved in presentation of antigen to CD4+ T cells.

The MHC gene family is highly polymorphic with more than a thousand different alleles found in humans.

Complex interactions between a persons genetic background and environment are involved in the development of MS.

Immune system plays a major role in MS.

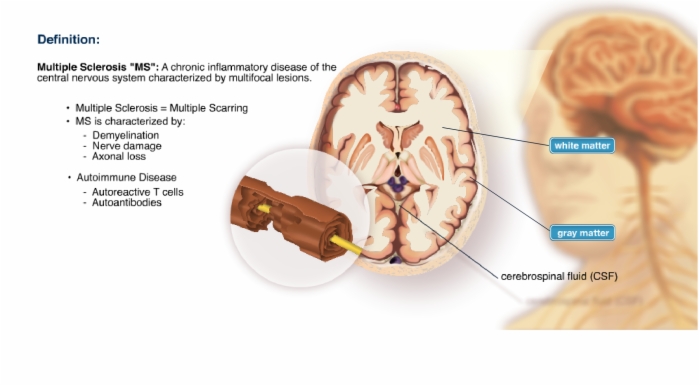

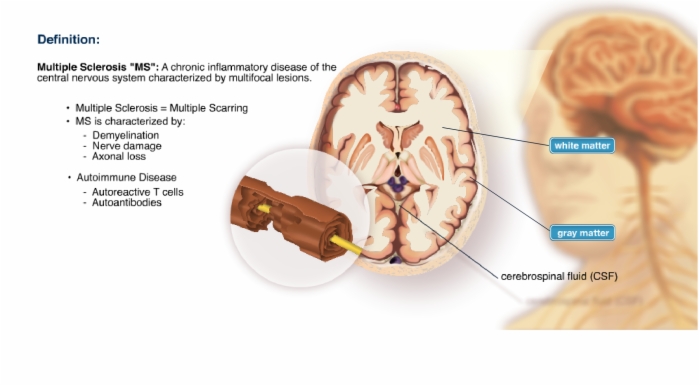

- Multiple Sclerosis = Multiple Scarring

- MS is characterized by:

- Demyelination

- Nerve damage

- Axonal loss - Autoimmune Disease

- Autoreactive T cells

- Autoantibodies

Most people with multiple sclerosis have periods of good health, or remissions, alternating with periods of worsening symptoms, or relapses.

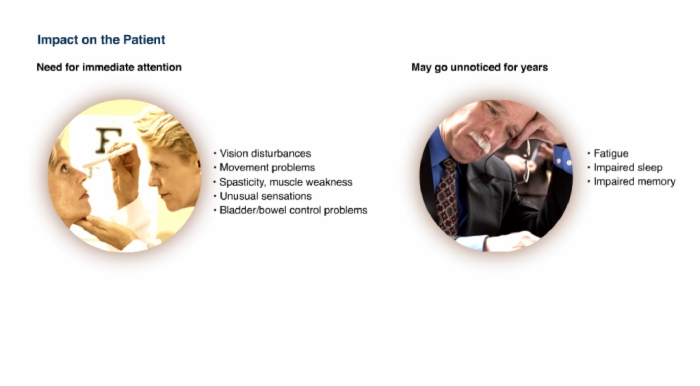

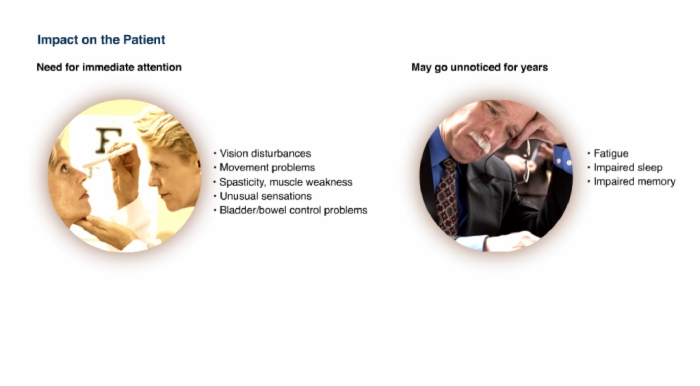

Initial symptoms could be:

- Vision disturbances

- Movement problems

- Spasticity or muscle weakness

- Unusual sensations

- Bladder/ bowel control

Vague symptoms can be:

- Fatigue

- Impaired sleep

- Impaired memory

Additional symptom:

- Heat intolerance

Progression of MS is unpredictable.

The clinical course varies from patient to patient, and symptoms may vary greatly within any patient over time.

Fluctuating symptoms result from damage to myelin sheaths and nerves, followed by repair or compensation, followed by more damage.

- The many MS symptoms can significantly impact patients' QOL

- Up to 60% of patients are no longer ambulatory 20 years after onset

- Impacts on employment and financial costs to society

- Physical, psychological and emotional effects

- Impacts on family and caregivers

- Patients should be encouraged to gain access to information, advice and education of MS (it's nature, treatment and methods to improve QOL)

Multiple Sclerosis:

- Common debilitating illness among young adults

- Approximately 400,000 people in the US have MS

- Approximately 2.5 million people worldwide have MS

- Prevalence varies greatly with geography

Important Points:

- Age of Onset

- Sex Distribution

- Geographical and Racial Distribution

- Mortality

- Typical age of onset: 20-40 years of age

- MS is more prevalent in women

- This trend may be on the rise

- Female to Male Ratios

In children, the female to male ratio of cases of MS may reach three to one, whereas in people greater than 50 years of age, the female to male ratio is approximately equal.

- MS risk may depend upon level of sunlight

- The further from the equator, the higher the MS risk

- Risk five times greater in temperate vs. tropical climates

- Risk is highest in Caucasians

- Rare among Eskimos, Bantus, Native Americans and Asians

Lesson Multiple Sclerosis is built from these main references. Log into SMi Source for a complete list and details.

Alonso A and Hernán MA. Temporal Trends in the Incidence of Multiple Sclerosis: A Systemic Review. Neurology. 2008;71(2):129-135.

Brissaud O, Palin K, Chateil JF, Pedespan JM. Multiple Sclerosis: Pathogenesis and Manifestations in Children. Arch Pediatr. 2001;8(9):969-978.

Campagnolo DI, Vollmer TL. Multiple Sclerosis (Updated Oct 4, 2006). eMedicine from WebMD.

Ebers GC. Environmental Factors and Multiple Sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:268-277.

Demetriou M. Multiple Sclerosis, Genetics, and Autoimmunity. In: Olek MJ, ed. Multiple Sclerosis. Etiology, Diagnosis, and New Treatment Strategies. United States: Humana Press, Inc; 2005:103-112.

Lassmann H. Models of Multiple Sclerosis: New Insights into Pathophysiology and Repair. Curr Opin Neuro. 2008;21:242-247.

Lazoff M. Multiple Sclerosis (Updated Mar 3, 2008). eMedicine from WebMD. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/793013-overview.

Marieb EN. Human Anatomy and Physiology, Third Edition. Redwood City, CA: The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company. 1995:346, 384, 390.

Murray TJ. The Palsy Without a Name: Suffering with Paraplegia 1395-1868. In: Multiple Sclerosis. The History of a Disease. United States: Demos Medical Publishing; 2005:19-60.

Medaer R. Does the History of Multiple Sclerosis go Back as Far as the 14th Century? Acta Neurol Scan. 1979; 60(3):189-192.

The Merck Manuals. Multiple Sclerosis (MS).

Miller DH, Leary SM. Primary-Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Lancet Neurol.2007;6(10):903-912.

Murray TJ. The Contribution of J.M. Charcot - 1868. In: Multiple Sclerosis. The History of a Disease. United States: Demos Medical Publishing; 2005:103-137.

National MS Society Fact Sheet. Available at: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/chapters/MNM/take-action/ms-awareness-week/Pressroom/Factsheetresearch/index.aspx.

Olek MJ. Differential Diagnosis, Clinical Features, and Prognosis of Multiple Sclerosis. In: Olek MJ, ed. Multiple Sclerosis. Etiology, Diagnosis, and New Treatment Strategies. United States: Humana Press, Inc; 2005:15-53.

Oksenberg JR, Baranzimi SE, Hauser SL. Biological Concepts of Multiple Sclerosis Pathogenesis and Relationship to Treatment. In: Cohen JA, Rudick RA, eds. Multiple Sclerosis Therapeutics, 3rd ed. United Kingdom: Informa UK Ltd; 2007:23-44.

Pirko I, et al. Gray Matter Involvement in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2007; 68(9):634-642.

Pyrse-Phillips W. and Sloka S. Etiopathogenesis and Epidemiology: Clues to Etiology. 1 In: Cook SD, ed. Handbook of Multiple Sclerosis, 4th ed. United States: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2006:1-39.

Ragonese P, Aridon G, Salemi G, D’Amelio M, Savettieri G. Mortality in Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. European Journal of Neurology, 2008;15:123-127.

Rosati G. The Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in the World: An Update. Neurol Sci. 2001;22(2):117-139.

Rubio JP, et al. Replication of KIAA0350, IL2RA, RPL5 and CD58 as multiple sclerosis susceptibility genes in Australians. Genes Immun. 2008; 9(7):624-630.

Skoff R. Morphology of Oligodendrocytes and Myelin. In: Herndon RM, ed. Multiple Sclerosis. New York, NY; 2003:7.

van den Noort S. Signs and Symptoms of Multiple Sclerosis. In: Olek MJ, ed. Multiple Sclerosis. Etiology, Diagnosis, and New Treatment Strategies. United States: Humana Press, Inc; 2005:1-14.

Vyshkina T, Kalman B. Autoantibodies and Neurodegeneration in Multiple Sclerosis. Laboratory Investigation. 2008;88:796-807.

Warren S, et. al. Mortality Rates for Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Worldwide: Geographic and Temporal Trends. In: Columbus FH, ed. Progress in Multiple Sclerosis Research. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Publishers; 2005:1-26.

Waxman SG, Craner MJ, Black JA. Na+ channel expression along axons in multiple sclerosis and its models. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004; 25(11):584-591.

WHO 2008 MS Atlas Report. Available at: http://www.msif.org/en/about_msif/what_we_do/atlas_of_ms/index.html.

Lesson Multiple Sclerosis introduces and defines these terms

MHCII - Major Histocompatibility Complex II.

Multiple Sclerosis: A chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system characterized by multifocal lesions.